When I was five my family added three Pekin ducks to our unofficial rescue operation. My mother invited my brother and me to name our new family members. “Bite-y!” My toddler brother declared, scowling at the duck that had just snapped his finger. And then he waddled off leaving the task of Genesis to me. Sacred naming. I turned to the other two and eyed them carefully. The bleary-eyed duck I called Zeus. He would perish later that same day, eaten by a snapping turtle in our pond. And the strong, assertive duck I gave my prized title: Aphrodite.

Already at five I knew that if I had a religion it was love and, recently introduced to Greek myths, I had immediately thrown myself at the feet of the goddess of love and beauty. Aphrodite was everything I wanted from a god. Sly. Capricious. Luscious. Powerful. It didn’t hurt that she also had one foot in my other favorite story – the little mermaid – as Aphrodite was similarly born of the sea, emerging from nacreous foam on the shores of Kythera.

“That duck is a boy,” my mom gently explained. “Do you still want to call him Aphrodite?”

“Of course!” I asserted, already aware that physical sex and gender identity had little to do with each other. Aphrodite the male duck felt entirely correct to me.

It wasn’t until years later that I learned my intuition that Aphrodite overflowed binaristic determinations of gender was substantiated. For Aphrodite, as the syncretic Greek version of the older Sumerian and Babylonian Astarte and Inanna, has never been a strictly female goddess. They have always occupied a place that, using the lens of queer theory, we can now label as somewhere between trans, non-binary, and intersex. Of course, each of these identities is quite distinct from the other. To be born intersex is NOT to be trans. To be trans is not to be non-binary. This terminology is modern and was not available 4,000 years ago when the female poet Enheduanna was composing the first poems to one of Aphrodite’s earliest avatars: Inanna. No one in the ancient world would have recognized these terms. But that does not mean that what they denote did not exist. This does not mean that in the ancient world where Aphrodite was worshipped and updated for thousands of years, gender – sacred and secular – was simplistically binary. In fact, archeological, textual, and iconographic evidence suggest that it may have been quite fluid.

Although Aphrodite is a late addition to the Greek Olympic pantheon (popping up around the 8th century BCE with one of her first mentions by Homer in the Iliad) this is not because they are a latecomer. In fact the worship of Aphrodite may predate the Olympic pantheon by several thousand years. Scholars have widely agreed that Aphrodite is a development of older love goddesses who share dominion of love, beauty, adornment, marriage, procreation, doves, the sea, and warfare. If myths are like mushrooms, above ground fruit that only superficially look like individuals, while originating from a larger fungal system below ground, then Aphrodite is a “mushroom” of a much deeper mythic mycelium. One that dates back at least 4,000 years to the eastern Semitic goddess Astarte and then, on the same rhizomatic continuity, to the Sumerian goddess Inanna, associated with early city of Uruk and the Mesopotamian Ishtar. Variations of this love goddess are inherited and adapted by the Assyrians, the Babylonians, and the Phoenicians. As happens with popular gods and goddesses, they are too popular to erase. Instead they must be syncretized and translated into new pantheons.

As the Sumerian goddess of love, justice, war, and procreation Inanna, we can see behind the bad paintjob of stable femininity. Inanna is no simpering goddess. In some of the earliest written poetry in the world, composed by the Akkadian high priestess of the moon of the city of Ur Enheduanna somewhere between 2285 and 22250 BCE, we hear Inanna called the “goddess of fearsome power”. Enheduanna writes: “ To destroy, to create, to tear out, to establish are yours, Inanna. To turn a man into a woman and a woman into a man are yours, Inanna.” Similar to Innana, we are told in the Babylonian Epic of Erra that the goddess Ishtar’s priestly retinue is composed of kurgarra and assinu “whose maleness Ishtar turned to female, for the awe of the people.” Innana’s servants were also sacred in that they had been “turned” by her. This was no curse. It was the ultimate divine blessing. For thousands of years Innana’s worship was presided over by a class of priestesses called “Gala” who were, for all modern terminology, identified somewhere between trans and non-binary. Men would “become” women and live as women in their role as a priestess of Inanna. They were seen as particularly “potent” beings – transcending binaries. They could undo evil, heal the sick, channel prophecy, and it was considered especially good luck to have sex with a member of the Gala according to an Akkadian omen text.

The thematic through-line of divine transformation leads all the way to the Phrygian version of the love goddess Cybele, flanked by her “castrated” priests. A Hellenistic poet Callimachus makes references to her priests as the “Gallai” drawing a link to Inanna’s priest/esses. There is much debate about what these priests actually did and if they were, in reality, castrated. Something that is important to note when reading ancient texts is that they are often biased, written by racist, homophobic victors, attempting to demonize another country or class of people they are trying to suppress. Much information about priests of Cybele, Ishtar, and Inanna, come to us via their detractors. Castration may not refer to literal castration. The use of the term may indicate that the Greek and Roman writers did not see these people as displaying a masculinity or gender that they recognized as “appropriate”.

But this bias doesn’t just live in the past. It is seeded in the present. Many people, including academics, have referred to the ability of Inanna, Ishtar, and Cybele to enact these transformations as evidence of their terrible nature. They see these transformations as a curse. This, seems to me, to be internalized transphobia. Why is it a bad thing to transition into your correct identity? If we look closely at the historical texts and evidence, we can see that this is the most sacred rite of all. To step into liminality was to offer yourself to divine service. Inanna/Astarte/Ishtar/Cybele transformed people into their true identities, apart from any biological characteristics. It was the most sacred initiation of all. The best proof of this is in the iconographic evidence of the goddess themselves. Many statues and engravings of Inanna show them with breasts and hips while sporting a curly beard.

This to me is the great gift of the goddess. Not to change you into the opposite gender, once again fully legible, but to place you in the fertile realm of blended “bothness” where you had the ability to adapt, change, and draw wisdom from multiple nodes of experience. Inanna themselves refuses to be fully defined. And isn’t that what it means to be a deity? To transcend? To transform? To transition? To live interstitially, inside the intelligence of relationships, rather than in the limited perspective of a circumscribed identity. Nowhere does this seem better demonstrated than in the early cult of Aphrodite, worshipped on the island of Cyprus. The Aphrodite of Cyprus is fully both, most often depicted smiling coyly with their skirts raised to reveal an erect phallus. Aphrodite has full breasts, sometimes a beard, hips, and a penis. We can see the direct iconographic continuity with their predecessors in reports from the Greek geographer and historian Pausanius when tells us that Aphrodite was often shown wielding the same weapons as Inanna, demonstrating their role as a deity of warfare.

The legend goes, according to Hesiod’s theogony, that Aphrodite was born from a profound “mixing”. This not heterosexual copulation. Instead her father Uranus’ testicles are severed and thrown into the ocean. Blood, semen, and seawater churn into a opalescent foam, and from this something equally mixed and indefinable is born: Aphrodite of Cyprus. Contemporaneous reports of Aphrodite’s worship tell us that they were worshipped by festivals of societal inversion, similar to the Twelfth night festivities of medieval Europe. Philostratus (190-230 AD) explains that: “The torches give a faint light, enough for the revelers to see what is close in front of them, but not enough for us to see them. Peals of laughter rise, and women rush along with men, wearing men's sandals and garments girt in strange fashion; for the revel permits women to masquerade as men, and men to "put on women's garb" and to ape the walk of women.” Macrobius write some years later, “There's also a statue of Venus on Cyprus, that's bearded, shaped and dressed like a woman, with scepter and male genitals, and they conceive her as both male and female. Aristophanes calls her Aphroditus, and Laevius says: Worshiping, then, the nurturing god Venus, whether she is male or female, just as the Moon is a nurturing goddess. In his Atthis Philochorus, too, states that she is the Moon and that men sacrifice to her in women's dress, women in men's, because she is held to be both male and female."

Aphrodite is lunar. And let us remember that lunar magic is decidedly ungendered despite its modern conflation with the feminine. The moon is always both. The crone and the maiden, the day king and the night queen, the non-binary bowl where everything mixes just like the ocean that mixed Aphrodite’s foam into form. Both shadow and glow play across the changeable face of a being that loves to live outside definition. The moon is mostly both, always trans: waxing and waning. The moon only ever flirts with fullness or emptiness for a brief, tenuous moment before slipping into change. Aphrodite as a lunar deity demands that we dissolve our edges rather than affirm them. Aphrodite shows us that if we look up moon night after night, dawn after dawn, we will see constancy that is not created by stability, but drawn into being by constant flux, constant transition. Aphrodite of Cyprus shows us that awe has no stable identity, no fixed category.

Later on, the Greeks, and then the Romans, will attempt to shave Aphrodite down to one gender, removing their connection to war, to mutability, to masculinity, to alchemical transformations. Just as the Romans were afraid of another gender-nonconforming deity Dionysus, so will they be afraid of the wild Aphrodite, inheritor of a feral magic capable of toppling empire. Unable to erase Aphrodite’s mutability completely, the Roman’s displace it into her “son” Hermaphroditus by the god Hermes, who will, by modern categories, seem to be intersex. But images of Hermaphroditus are clearly updated versions of the earlier Aphrodite, even performing the same “skirt lifting” gesture. Not only is Aphrodite fractionated in terms of gender in tehir Greek form, they are also metaphysically cloven into Aphrodite Uranios and Aphrodite Pandemonium. They are the heavenly spiritual goddess of love and the goddess of the people and their physical urges and desires. Here we see the early inklings of the split that will become rearticulated as spirit and body, and Cartesian mind and matter.

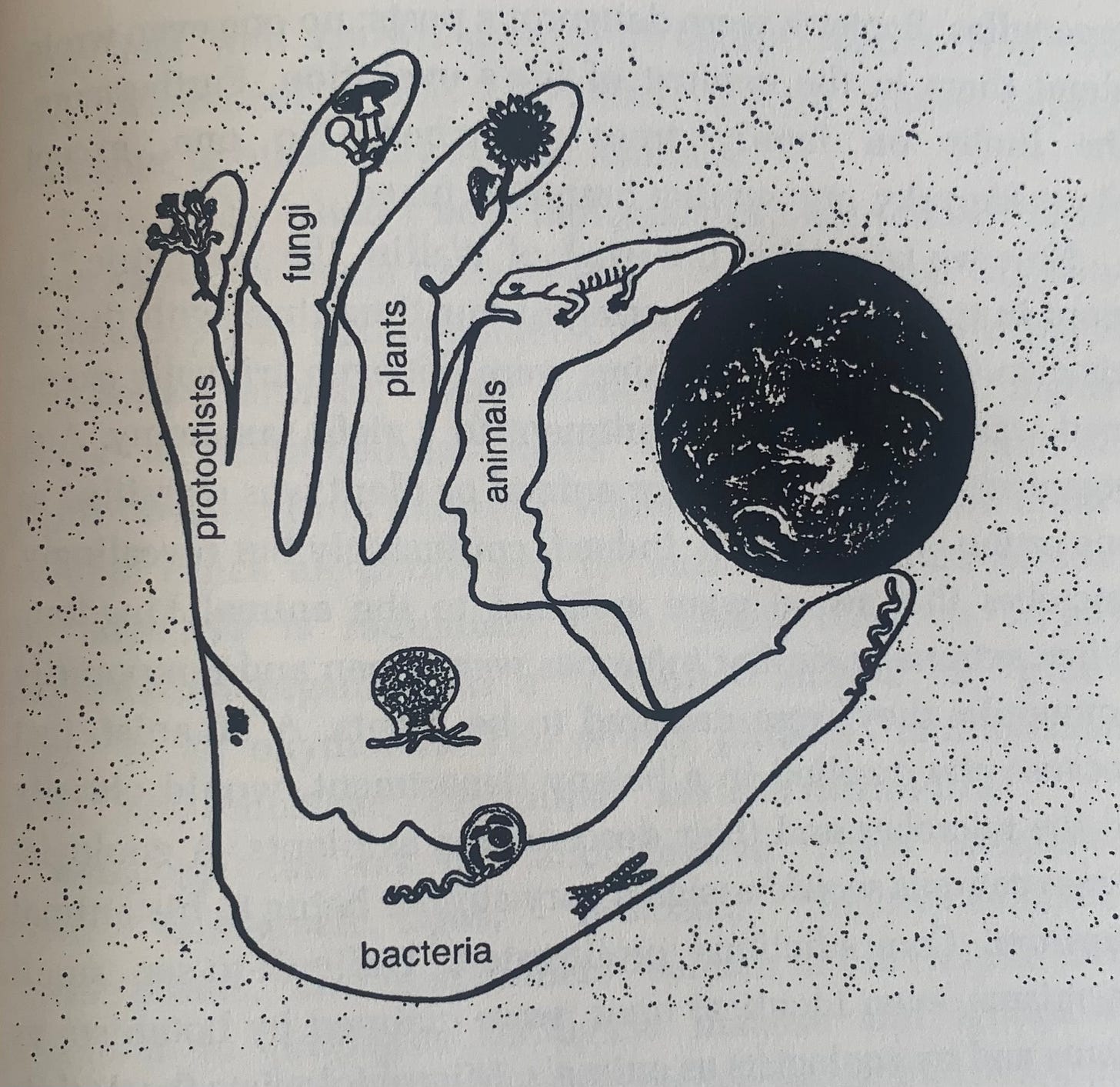

As I have been researching Aphrodite, I’ve been simultaneously reading about the symbiotic origins of multicellular life in the work of biologist Lyn Margulis. One of my favorite ways to write is to pay attention to the moment when two seemingly unrelated passions begin to intertwine and fuse into a fresh narrative. As I’ve been following both of these separate strands I’ve been increasingly aware that Aphrodite, to me, seems less the goddess of human lovemaking, and more the goddess of the symbiotic fusions between species that create biological novelty. Aphrodite presides over a romance that transcends anthropocentrism. Or perhaps predates it. The fusions of simple prokaryotic cells, driven by hunger and desire to connect, to create the complex nucleated cells that build our very bodies today. Margulis describes, “In the great cell symbioses, those of evolutionary moment that led to organelles, the act of mating is, for all practical purposes, forever.” Life is driven by these complicated and surprising “interweavings” that seem to embody Eros without strictly mapping onto a human narrative of copulation. Lovemaking that doesn’t result in a couple. But in a new being entirely.

Image by Shoshanah Dubliner

It is interesting to note that just as our microorganism ancestors emerged from seawater and made it onto dry land, so does Aphrodite emerge from the ocean, too, one foot in liquid microbial prehistory, the other in solid ground mammalian existence. In her book Symbiotic Planet, Lyn Margulis explains, ““Symbiogenesis was the moon that pulled the tide of life from its oceanic depths to dry land and up into the air.” And if Aphrodite is the moon. Then Aphrodite is the moon of symbiotic mergers. Like meiotic sex, the kind we as humans engage in, must have at some point originated from another simpler form of sex, not involving two genetically different partners, so does Aphrodite emerge not from a heteronormative conjugal act, but from a splicing off, an accidental castration. They spring from the spermal foam of their father’s castrated member. The goddess of divine lovemaking comes from an act that is more anarchic than sexual fusion. It harkens back to those prebiotic days, greasy lipid bubbles accidentally sequestering polymers and chemical reactions, before dehydrating and breaking open, releasing matter. In and out. Academic and Neuroscientists Terrence Deacon and biologist Lyn Margulis both muse that it was these early “grease bubbles” that first imitated the semi-porous container of a cell. For life is, at its most basic, a cell. A semi-permeable container that constitutes difference: inside and outside. Self and environment. How these bubbles became sentient and began to self-replicate, how they eventually integrated into multicellular beings capable of terraforming the earth, is another problem entirely. But at its most basic we can think of Aphrodite as being the exultant, non-sexual offspring, of one of these early cells rupturing and reproducing accidentally as it accommodates shifting climatological pressures.

Aphrodite seems to me to be a useful deity for moments of transition: personal, political, and ecological. The fiction of a stable identity will not save us in a moment of climate collapse and mass extinction. The idea of a stable species is fictional if you look through a wide enough lens. We are always adapting, evolving, changing, fitting into shifting ecological niches. And the most useful tool we may have moving forward may be that of “bothness”. Of liminality. Of being able to fuse and merge and embody multiplicities.

Sources:

Venus & Aphrodite: History of a Goddess by Bettany Hughes

Symbiotic Planet by Lyn Margulis

The work of the Queer Classicist: www.thequeerclassicist.com

Morgan, Cheryl. Evidence for Trans Lives in Sumer. Notches:http://notchesblog.com/2017/05/02/evidence-for-trans-lives-in-sumer/

Roscoe, Will. “Priests of the Goddess: Gender Transgression in Ancient Religion.” History of Religions 35, no. 3 (1996): 195-230. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1062813.

Lancellotti, Maria Grazia. Attis, between myth and history: king, priest, and God; Volume 149 of Religions in the Graeco-Roman world. BRILL. pp. 96–97.

Jastrow, Morris (1911). “The ‘bearded’ Venus”. Revue Archéologique, 17, 271–298. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/41021741

Wolkstein, Diane & Kramer, Samuel Noah (1983). Inanna: Queen of Heaven and Earth, HarperCollins, New York.

Michalowski, Piotr (2006). “Love or Death? Observations on the Role of the Gala in Ur III Ceremonial Life”. Journal of Cuneiform Studies, Vol. 58, 49-61. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/40025223

The work of poet Jonah Welch is a great alchemical crystallization of Aphrodite/non-binary wisdom. Support Jonah’s work at https://www.patreon.com/jonahwelch and https://www.jonahwelch.com/

And the amazing podcast Ancient History Fangirl.

this is feeding me so so deeply Sophie. thank you for weaving together so many of the things that feel like deep nourishment for me, and for so many others.

Genius. Boundaries disssolve and evolution takes quantum steps. I bow before Aphrodite.