“I hope you’re feeling better!” exclaims a friend in the grocery store.

“What?” I shake my head with disbelief. I’ve shared my diagnosis with this person after all.

Do I tell them that I had to pull over twice on my drive into town because I thought I might faint? Do I mention this week’s doctors’ visits, blood draws, cat scans, and insurance phone calls? I have an incurable connective tissue disease—with an ever-growing laundry list of complications and symptoms. Do I open up to this person, standing there amid the produce in the supermarket, how rare it is that to have these issues reversed? Do I try to talk about the ways I summon vitality even when I don’t have it?

“You must be feeling better! You look great! Your hair is so long!” We make our way to the check-out line.

Actually, my hair is falling out but I style it expertly. I spent an hour on my makeup to disguise my pallor. Can I still try to look beautiful even if I am sick? Or do I need to perform my illness to remind people what is going on with me?

“You remember how I said my condition is incurable?” I ask, no longer able to maintain the cheery fiction that I am progressing into health and wholeness.

She frowns.

“I’m feeling a lot of things. But I’m not feeling better. How are you feeling” I ask as she splutters, confused that I’m not playing into the well-worn script of recovery and optimism.

I hope you’re feeling better. We’ve all heard it. We’ve heard it earlier in the day when we were on the phone with insurance companies trying to get a procedure scan covered. When we were up all night vomiting, trying to gauge whether we even had the energy to make it to the emergency room. We hear it when we face permanent disability and shortened lifespans. We hear it when we have received a diagnosis with no cure and no comprehensive treatment. We hear it from loved ones when we are in the midst of pain that never resolves or abates.

Over the past fifteen years of chronic illness, I have come to realize that the statement “I hope you are feeling better” is symptomatic of our culture’s inability to witness suffering and illness and death. If someone has recently had the flu or a virus, it can be compassionate, but for those of us who cannot be cured it negates our experience and feels hostile. We cannot perform the healing narrative that other people, panicked by the sense that something might not have a neat or happy ending, require from us.

My friend’s insistence at the grocery store may come from a desire to see me well. But it is also, simultaneously, a way of erasing the intensity and nuance of another person’s lived experience. It is this same impulse for easy fixes that fuels a self-congratulatory environmentalism that is looking for “good signs” instead of understanding with depth and care the cascading crises we are confronting.

Just as we are uncomfortable with other people’s illness, other people’s dying, so are we uncomfortable with the environmental devastation and cascading societal pain all around us.

Do we go outside and say to the clearcut forests, the poisoned ecosystems, the microplastic-threaded oceans, and say, “Hope you are feeling better!” If we can develop a greater capacity to witness and accompany pain and illness in each other, we might become more sober and compassionate in our assessments of our own environmental entanglements. In the words of Donna Harraway, can we stay with the trouble?

When we say to someone who has been clear that they have an illness, a chronic illness, a tricky prognosis, or even a terminal illness, “I hope you’re feeling better,” what we are really saying is, “I want to discharge my social responsibility—but I find you, the sick person who cannot be cured, scary.”

What we are really saying is, “Perform wellness for me. Make me feel better.”

But many of us cannot perform this easy ascent into recovery. We cannot get better. We need to problematize our discomfort with people who do not follow a standard healing arc: illness, diagnosis, and recovery. What if we can’t recover? What if we can’t reenter the kingdom of the well? How do we stay with that complexity and witness it? When we are life-threateningly ill and someone says, “Hope you’re feeling a bit better!” we are being covertly asked to perform a fictional story of healing. And the reality of our experience is expertly erased to appease a well person’s discomfort with disability and illness that renders us illegible, outside the normal plotline.

Next time we feel compelled to say this to a person navigating complex and incurable conditions, we need to take a breath and think about what it really means. A more helpful thing to say is, “How are you today? How are you managing? What is today like for you?”

I am not feeling better. And I may feel worse. But I am feeling with every part of me. Can you feel with me?

___

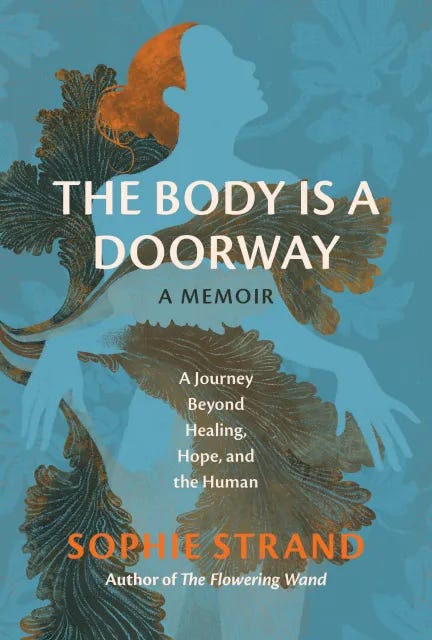

The Body Is a Doorway, my memoir about ecology and chronic illness that asks the question, “Is there a story beyond our expectations of health, wholeness, and happy endings? What spectrum of joy and aliveness is available for the incurable and the chronically ill?” has been out for over a week! Thank you so much for the letters and responses that have flooded my inboxes. They convince me that no matter how raw and scary it has felt sharing work this personal, it is worth it. I love you all so much.

I feel your love for the Earth and for Her whole cosmic society—all our relations—and I am deeply grateful for you and for this palpable love in which I share!

I am feeling WITH you, dear Sophie, and my heart is filled with love and respect for the way you handle this. You’re an inspiration to others.