Magic as radical embedding in our web of relations

Revisting a 2022 Samhain conversation with David Abram

Lord of the Rings Illustration by Roger Garland

Sitting here on election day watching the crows explore the white flesh of the November sky. We are in a serious drought in the Hudson Valley and everything feels exposed and brittle. Not unlike the collective spirit. A touchstone of sanity in the last month has been conversations with my good friend David Abram. Unfortunately none of those made it onto paper or public record but I’m returning to a conversation we had back in 2022 about magic in preparation for my Advaya course Rewilding Mythology. I’m offering an excerpt here as we all try to weather whatever storms are brewing.

SOPHIE STRAND: It's so interesting—I feel like it's something I believe in so intensely, and yet, when you go to pin it down, like a butterfly, you kill it. So, I think you have to kind of have a cataphatic experience of it, you have to name it again, and again, and again, in order to in any way, try and actually delineate what it could be.

But for me, I was thinking that there's a modern idea that magic is above the world of material or natural order. That we have the world of science where everything is quantifiable, we can measure it, we understand the rules. And then there's magic, which breaks the rules. I was thinking that I very much disagree with that. I think that magic is actually the deeper layer of rules, it emerges, that can't be quantified, that it's inherently irrational. In a certain way, it gives us space, that we can't actually understand everything, but there is a deeper order, an order that confounds our idea of order.

And when it emerges and erupts through that texture of anthropocentric, quantifiable rules, it gives us a moment to breathe and say, the world is bigger than our machines. I was actually just rereading this essay, I'm sure you've read, that I love, "On Fairy-Stories", by Tolkien. And Tolkien has complicated feelings about magic, but he explains these magical moments that happen, [and] it's not that they rupture the order, they're never a god from the sky—those don't really count as real magic, because they disrupt the actual natural order. That they have to be part of the world.

So in Lord of the Rings, when the golden eagles come to save Frodo and Sam, that's magic, because those eagles are part of the world. Their timing, and everything is inherently deeply unpredictable and magical—you don't think they're actually going to come.

But they're not a god from the sky. They're not rupturing the order, they're coming up from a deeper order, that's well below what is visible to the human. So that's what I've been feeling: when something magical happens in my life, it's a deep sense that there's an order well below the order that structures my days.

DAVID ABRAM: Lovely.

SOPHIE STRAND: Your whole life has been about magic. So I'm interested in how it's resonating for you today.

DAVID ABRAM: One of the ways, sparked by what you were just saying, the sense of magic as another order, I do feel it's a particular logic. The way of things. Magic to me, is really the way of things. It's how things happen.

When we experience the world, from a fully embodied, embedded position, in the depths of the world's ongoing unfolding, that the world seems to follow a much more cut and dried, straight line, linear, right-angled logic. When we, and only when we, look at or ponder the world from a kind of disembodied gods-eye viewpoint hovering outside the field of the 10,000 things, gazing upon the world, seeing it, as a spectator looking at a spectacle, which can be then framed as a set of objects. Some bigger, some smaller, some more complicated, some less so. But it's basically a set of objects and objective mechanical processes, just automatically going about their thing.

Magic, on the other hand... And if that linear logic is the one that leaks out from ever so many papers in the sciences, even and still today, it's this strange rhetoric that is always taking its distance from the world, assuming that we can ultimately "figure out" what it is, how it all works, ultimately. But magic is just this very other logic, from the perspective of a creature from the perspective of a bodied being, like you, like me, down here, in the depths of this blooming, buzzing proliferation of colour and shape and texture and olfactory essences, riding past our noses, wherein some things are always hidden behind other things, because we're down here. And as I shift my position, and perspective, new things become visible and other things are now occluded or hidden.

Magic is the logic of the world, when the world is experienced from within its own depths. And in this sense, maybe "logic"'s not quite the right word, it seems to me, when I'm trying to describe a logic that I don't deploy from outside, like with my head, but that I'm inside of, I'm immersed in it, and move within it bodily. That seems more to me, like logos. Logic is a logos.

It's a strange logic that catches me and moves me, and it's weirdly richly participatory at every moment.

SOPHIE STRAND: What was really striking me is there's something about magic, I think, that we both experience, which is related to culpability, and to relationality, you're responding and response-able, you're able to respond, you're also responsible to the world, in a way that you can never do when you're in a laboratory experience, where you're watching the billiard balls follow your own trajectory.

And it's interesting because the god's-eye view, we're seeing more and more, involves a type of magic, which is, when you pretend that you have the god's-eye perspective, and you can watch how things happen, you're actually affecting how they happen. Which is such an interesting idea, that even when you think you're at a remove, your idea of your remove, changes the outcome.

DAVID ABRAM: Yes. So here's another take. I don't know if this resonates at all. It's been with me for a while, but just a sense that magic is a particular form of mysticism, that every one of the world's—what we speak of as the world's—religions has at its heart. [Each one has at its heart], a mystical tradition: Kabbalah for the Jewish tradition, Sufism for the Muslim world, for the Islamic world, there's the many different Christian mystical traditions.

But if at the heart of every world religion is a mystical tradition, at least one or many, then at the heart of the mystical traditions, one finds—always—the magical tradition, which is a particular form of mysticism. It's the mysticism of this world, of the body's world, the body's engagement with the Earth around it. It's a mysticism that has no interest in transcending the body, or transcending the material world, with its folds and fabulous unfurlings, but is actually interested in staking its claim, or holding its place, down here, in the material thick of things.

To the point where each thing, each acorn, each slab of sandstone begins to shine, that the world in its material presence begins to become luminous, darkly so, sometimes richly shadowed, yeah, but each thing, vibrant and open-ended, and disclosing its own interior animation, its own pulse, its own rhythm, or rock, and roll.

In that sense, a particular form of mysticism, that those who are drawn to magic are those drawn to this sense of affinity with their own thingly material density and weight, and have no wish to transcend their flesh but are interested in inhabiting it, becoming more and more of it, from which they sense that their culture or their language has estranged them from their bones, and their animality. They are folks who are busily becoming more and more animal, more and more creaturely.

SOPHIE STRAND: I love that. I studied in college, and I've continued to write and think about the female mystics in the medieval ages. They were exiled from ecclesiastical and Scholastic religion, so they were very focused, their bodies became the site of ecstasy and spiritual exploration. And so their visions themselves were incredibly sensual and creaturely, that they were climbing into Christ's wounds, that they were having these orgasmic experiences, and very often, they were having convulsions and physical experiences as well.

And that was what made them so terrifying to the church, [it] was that their experience of mysticism was highly sensual, highly embodied, thinking about Hildegard of Bingen, and God showing her that all of life was just like a nut in her hand, that it was a tiny piece of condensed matter. And thinking about like, yeah, mysticism is not the moment when you transcend, but it's the moment that you're like, the whole world is a nut. It's a mustard seed. It's right here. It's tactile, I can put it in my mouth and suck it to know it, that there's a way of knowing that has very little to do with sensemaking and has very much to do with sensual making.

DAVID ABRAM: If that does make sense, I wonder and I've wondered for a long time, if this particular form that lies at the core of each of the mystical traditions, this magical tradition, it's actually really, almost always, a holdover, pre-religious, indigenous, animistic, modalities of experience, common to the particular place, to that particular terrain or landscape. And hence, it's carrying practices, bodied practices, that are often very basic and intensely practical and pragmatic about how to live in this land.

How to generate heat within your body, from your belly, in times of excruciating and unending cold? Or how to douse for water in the depths of an ongoing drought? [These] very practical, bodied practices, not just bodied, but they're always about the body and its relation to the larger body of the world, or of the Earth. So we've got these world religions, we've got these mystical traditions, at their heart, these magic practices, many of which are holdovers from the pre-religious world that were just very basic to living, and getting on in that land, at that time.

SOPHIE STRAND: So the area that I've written about a lot is Jesus as a magician, Yeshua, and from being from Galilee, which is outside of the city, outside of the Scholastic Judaism, which is much more associated with folk practices, that people who are being oppressed by empire, who've been dislocated, who have had their land taken from them, who are incredibly sick, and then traumatised, are trying to make do, and they don't have time for actual scholarly experiences, they need to take care of the body, first and foremost. And so there's a scholar who I've learned a lot from: John Dominic Crossan.

He does a great case study, from all the anthropology and all the primary documents of magical practices in Second Temple period Palestine, and he says the only difference between magic and Orthodox religion, is magic is what is called the little tradition. It's what the peasants have to do to keep alive, they don't have time for the act of religiosity like because they're actually trying to be bodies, they need to make food, they need to heal their sores, they need to make sure that their wife survives childbirth. And I do think that there's something to be said, which is, magic is very, very much about staying alive, that it's very wedded to survival.

But religion is almost an elite practice. It's a luxury. And it's interesting that religion has become the dominant theme, when it's not actually practical, in terms of: how am I going to find food? How am I going to grow food?

That when you look at magical practices, it's about: how can I be attuned to the seasons? How can I be attuned to my own body and relationship to the season?

DAVID ABRAM: How can I find water?

SOPHIE STRAND: Exactly. And [we're] at a moment in time where, because of climate change—[and] we're kind of siloed from being affected by the weather, by the seasons, by agricultural patterns, but—we're going to be more and more sensitive to those. And I think perhaps it's that understanding that's pushing people towards magic.

DAVID ABRAM: Yeah. And yet, in the culture at large, there still and has been for many long centuries, a deep revulsion, a fear of magic. Just as there's been a fear of the body and embodiment—something about being whatever else I am, if I'm a body, I'm subject to all the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, I am vulnerable, I am going to die.

And that seems disturbing to lots of folks but to me, it's even more what alarms folks, is just that present moment vulnerability in the ongoing interchange with others, with other persons, other beings, who might see me as too fat or too skinny, or not quite the right way. But I'm vulnerable in ever so many ways to illness, to disease, and all these ways wherein we take flight from being creaturely, because there's something terrifying about it.

It means that we don't have the world under our belt, that in fact we are subject to so many things that are out and about—some of which can eat us, really big things that can chomp us down, and even some really small, unseeably small, beings that can take us down. And so, it's too darn terrifying, [so] I'd like to imagine myself into some much more pristine mode of being.

SOPHIE STRAND: Yeah, I think a theme that feels like it's emerging is that magic is about making oneself vulnerable to the elements and to other beings. The moments in my life that I would uncontestedly say were magical, were moments when a creature, some kind of animal, bird, bear, contacted me in a way that felt dangerous and risky. And I was being asked to participate in a story, that I would never be able to actually see. I think that their magic is when another being comes and says, will you be a conduit for me? You're never going to know what you're doing. But will you do it?

Roger Garland

You said at the beginning, that magic is a way of making things happen. Magic is a way of letting your body be the billiard ball, as part of the universe. You don't know what your forces [are] pushing forward, what your trajectory is igniting. But you let that bear that came and looked at you, move through you and use you as an instrument. So yeah, I've been thinking of magic as a way of saying, alright, I will be a tool, use me as a tool, use me as an instrument. I'll play music that I'll never actually be able to hear.

But that's a terrifying thing. You think of the ant that gets taken over by cordyceps and becomes a vehicle for the fungus. I think that's pretty magical. But it's magical in a way that's much bigger and riskier, than our simplistic binaries of good and evil.

DAVID ABRAM: Yeah, for sure. I mean, in a sense, we're speaking here about magic as as interspecies communication. As the ability to step out of the singular umwelt of one's particular species and make contact with another shape of sensitivity, another style of sentience, which verges on—and I mean, let's keep holding all these things close—what for me is maybe the most profound sense of magic... came from my time travelling as an itinerant magician. I have to admit, some folks listening will know this, but others won't: my fascination with these matters came from my craft, as a sleight of hand magician.

I was a magician by profession for many years, I put myself through college performing as a magician. I was house magician at Alice's Restaurant, which is a very storied establishment in the Berkshires of Massachusetts, and then began performing as an itinerant magician around first New England, and then around North America. Took off a year after my second year of college, and travelled as an itinerant magician through Europe, and a bit of the Middle East, back, finished my degree and then took off, journeying again as an itinerant magician through Southeast Asia, through Sri Lanka, through Indonesia, through Nepal, looking to meet the traditional Indigenous magicians who practice their craft in various village backwaters, in those cultures.

But I was approaching them not outwardly as a researcher, or an anthropologist, but as a magician in my own right. Someone very gifted in the skills of sleight of hand, but I was curious, would that be at all interesting to traditional magicians or shamans or sorcerers, as we sometimes speak of these folks? Would it be enough to pique their interest? And in fact, it was, and I got in way over my head, drawn into the homes of a number of these exceedingly bizarre individuals called dukuns, in Indonesia, and called jhākris, in Nepal. [I] asked to trade secrets with them, and ultimately to participate in their ceremonies.

And like I say, yeah, I got in too deep for my own good, perhaps. But it sure turned my life on its head. I undertook that journey among them to study the uses of magic in medicine, folk medicine, in curing, but this morphed, profoundly, into a much deeper concern with the uses of magic as a way of communicating with other animals, with plants, with the forest, with the valley, with the wetlands, that is, the magicians I came to know, this tiny clutch of folks that I had the luck to learn from and live with, in very different cultures.

But it turned out that although they were the healers for the villagers in their vicinity, they understood that their more primary role or function was to work as intermediaries between the human world and the more-than-human collective. The more-than-human collective, not meaning in this case, anything supernatural, but meaning the world of the humans, but all the other walking and crawling folks who move through the local landscape, as well as the flapping and squawking wingeds overhead, and the swimming folks in the waters around the islands of Indonesia, but also the rooted powers, the plants, the herbs, trees, whole forests, all assumed to be alive, awake and aware, but not just what we take to be alive. Also, the river, the dry riverbed, the clouds drifting overhead, storm clouds, in a big way, which are often called and invoked to drop rain, the mountainsides, rocks, anything that we can sense was assumed to be sensate and sensitive in its own right.

And the magicians, it seemed to me, Sophie, were those folks who were most susceptible to the call of these other-than-human styles of resonance and vitality.

The magicians were the sensitives, those who were most susceptible to these other-than-human solicitations, who could pick up from these other beings an easy resonance, or a reverberation within their own organism. And this enabled them to work as intermediaries.

In fact, these folks would be helpless in the middle of the village. Because other humans whose nervous systems are shaped just like their own, are too similar. And they pick up way too much from other nervous systems, that are their own shape.

But this kind of sensitivity was just right for entering into some kind of communication with a frog, or with a spider, or a squirrel, or a wolf, or a forest. And that became their primary role or function, within their communities, was to tend to that boundary between the human world and the more-than-human world. And in that sense, it does seem to me, that magic in its uttermost essence has everything to do with the encounter with another style of intelligence, the ability to negotiate the strangeness between the human and an other-than-human shape of experience.

SOPHIE STRAND: I love that. So many things came up for me. One is that we're in a moment in time where neurodivergent, whatever that is, is highly problematised or sensationalised, that it's something you have to work with, you have to change, until you can come back into a normative mode of participating in culture, but thinking about how I'm a survivor of early trauma, which opened up the gates. So instead of homogenising the sensory stimuli I receive all the time, in order to function within human society, I noticed way too many frogs and crows, and landscapes and that the world is talking all the time, and I can't shut it out.

And I was just thinking that, there are so many people I know who feel like they're way too sensitive, that their brains are too alert, they have ADHD, they have all of these things. And in a very different time, that would be a mode of knowing, a way of actually realising that the world was speaking. And that maybe you should be paying attention to all of those different voices. So I think what I'm always trying to do in my life is say, okay, yeah, my nervous system is very primed and awake, I notice all the fluctuations in temperature and pressures, I notice all the birds, the shifts, and I can't not notice, and it's way too much information.

And yet, perhaps it's that kind of fluency that is necessary. Some people need to be that intermediary. And there are a lot of people right now who think they're a problem. But really, they may be very, very attuned to magic. It's all about start[ing to] think about it a little bit differently, and reframing it.

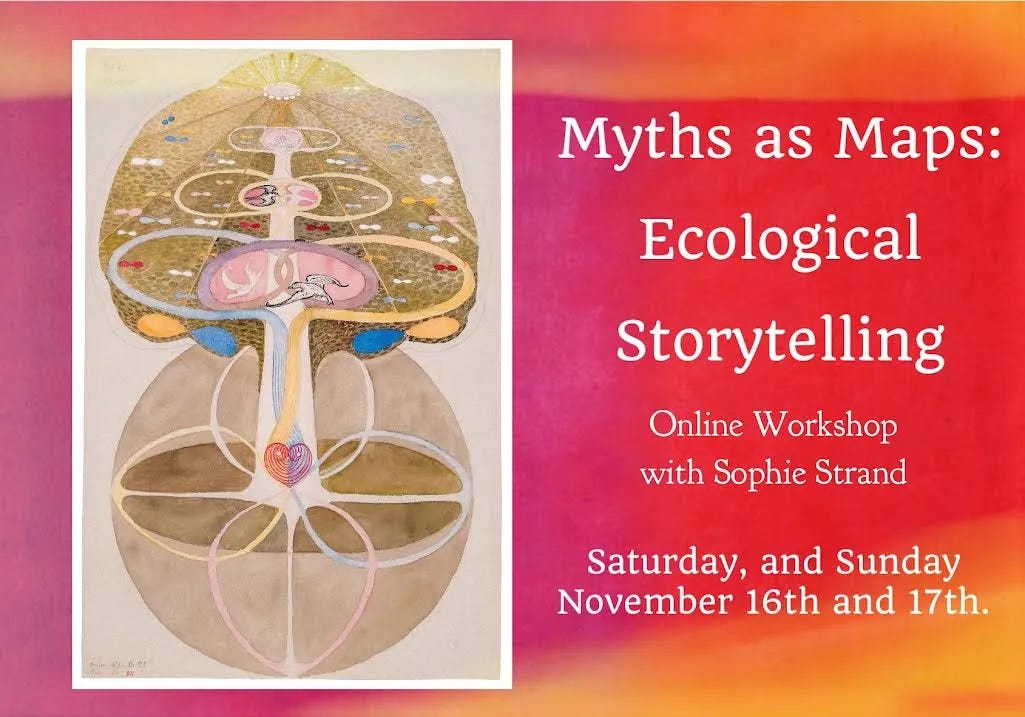

I’m offering a weekend workshop in November! You can sign up and read more on my website.

This has been the free version of my newsletter. If you choose to support the paid version of this newsletter, you will receive at least two newsletters a month featuring everything from new essays, reflection on writing craft, poetry, excerpts from my upcoming books and projects, mythic research, reading lists, poetry, book reviews to ecological embodiment exercises, playlists, personal updates, and generally a whole lot of funk and texture.

I am overwhelmed with gratitude by how many of you have showed up here to support my work and widen my thinking. Right now you are literally keeping me alive and funding the out-of-pocket medical expenses that allow me to receive IV nutrition and connective tissue specialists.

I am grateful in a way that is wide and deep and low. I hope you can feel some sonorous note of it - the hum and grind of ice relaxing under the sun - in your body. I am sending the song of my thanks your way. I love you all so much.

Thank you so much for sharing this wonderful, magical conversation with you and David! It’s perfect for today, and got my day started off with exactly the perspective and energy I needed. Being, you know, that today is so fraught, like, as so many memes have said over the past few days, we have been waiting for the “life or death” prognosis. Regardless of what happens, we have magic and I know these times, as anxiety-ridden (for me anyway) as they are, also somehow stimulate the nerve endings and kind of force me to remain open to other voices, other vibrations, the real reality within which we live. I wanted to find a “quote” here, to share and as I kept reading the whole piece is one magnificent “quote”. That there are so many increasingly sensitive people now, not only recognizing their “neurodivergence” but claiming it. And it seems to me that the world we inhabit now, the chemicals and losses and how these are literally changing our DNA now and for the future, it feels necessary somehow. Part of evolution. We’re on a certain trajectory . . . those of us who can engage with the more than human voices and energies . . . are essential.

David’s work has had a huge impact on my life and work since I first met him in the 1980s. I remember seeing him performing his magic while talking with someone on the porch at the main building at Omega. I had written to him but had not met him, and it seemed so purposeful, the meeting. And then his amazing work with the All Species committee at the Bioregional Congress, which led to one of the most magical and important experiences I have had in my life, that I have carried with me and shared over and over again as “proof” that indeed it is possible, and necessary, to include ALL voices in our human deliberations. . . . So thank you (and David) for putting this out there today as a reminder, to me anyway, that Magic is where it’s at. 💖

I've been a big fan of David Abram for years (Spell of the Sensuous & Becoming Animal). On Samhain I stumbled on your video interview with him from 2022 (https://www.facebook.com/share/v/186ViY1ta9/). And now it appeared on your substack. Love the way the neural network of the universe brings me what I need. A bow to synchronicity.