Sacred Negative

Evolution & Ecological Embeddedness

I am flooded with rage beyond expression. I’m waiting until my anger is cleaner to speak (nod to Resmaa Menakem ) and my body is a bit hardier. As a survivor of CSA and sex trafficking, the revelations of the past week and the complete absence of any kind of adequate response has been ringing my body like a bell. I’m not surprised I’m in a full physical flare. I know so many of us are navigating this tangle of physical/ historical response and desire to act right now without any clarity of how to best move. I’ll say only this for now, I’m looking to the bonobos.

While I try to metabolize this toxic sludge to the point where it can turn me into a radioactive supervillainess capable of toppling empires, I’m offering this updated meditation from an early draft of The Body Is a Doorway on evolution and embodiment.

Sacred Negative

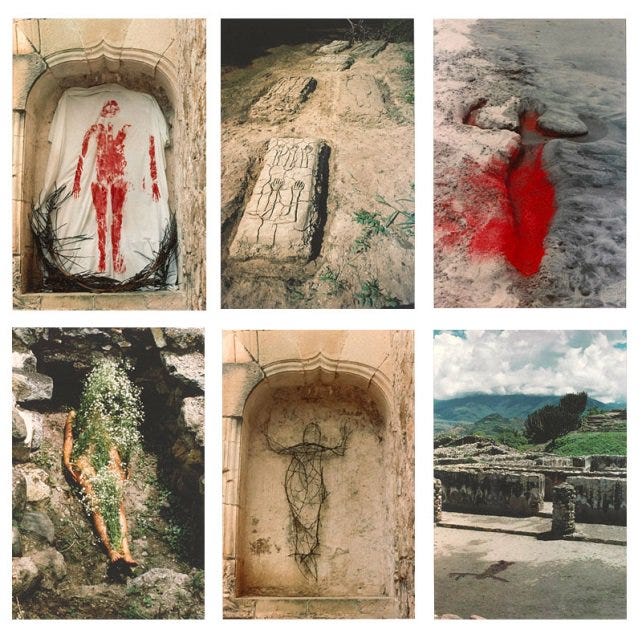

Sedimented with pollen, blurred by brine, the footprints are still decidedly human. Unearthed after a storm at the Happisburgh archeological site in England, the bipedal tattoo has been dated to around 900,000 years ago. Strange to think that the way these ancient ancestors have reached us is not through their brute material, but through their carefully held absence. A foot-shaped void. Almost a million years later, in 1973, the Cuban-American artist Ana Mendieta created a corporal dialogue with nature Siluetas, carving female silhouettes into mud, meadows, grass, and sand. Like the million year old footprints, these human-shaped holes gathered rainwater and red clay. Struggling to articulate the anguish of exile from her homeland in Cuba, her direct experience of colonialism and sexism, Mendieta rooted her very shape into the ecosystem not by virtue of a seed, but by the practice of hollowing out. An intentional creation of absence.

Paleolithic handprints sting the intestinal curvature of karst caves. Ancient circles of charcoal tell us where something was burned to cinders. Where matter was spent. Cooked. Sent skyward as sparks. Where absence bloomed into an ashen reminder of past gatherings.

Human beings leave a mark. But, it is important to remember that human beings, ourselves, are a mark that has been left.

Evolution moves at so slow a pace that it is hard to comprehend. Genetic traits are selected for not in one generation, but over the course of hundreds of generations. There was no first human and last monkey-becoming-a-human. There is only one pulsing river of becoming. The body you have today is not the product of a quick, tidy experiment in upright, large-brained hominids. It is not even adapted to your present environment. In a certain way you are already out of step, materially obsolete, already an experiment in adaptations that is sending genetic information into the distant future.

Your body is a love song to a lost ecosystem. Your eyes were first developed in the penumbra of the Cambrian explosion, fitting into a seawater niche that they no longer blink through. Your eyes were crafted to see beings that no longer exist. Is the inky iris at the center of your sight an ode to those extinct witnesses? Does your sight, like the spokes and hubs around a wheel, depend on absence? Does it remember that it was developed to see corals? Arthropods? Trilobites? Viridian cyanobacteria growing like dragon skin across the oceans? Further on, our long arms and curved fingers were made for tree climbing, for manipulating vines and branches. Our bodies are the photo-negative of these lost forests.

The morphology – the shape and function – of our bodies evolves by way of environmental embeddedness. If you can find a niche, a way of surviving and reproducing and nourishing yourself in a relational context, you pass along your traits to the next generation. Thus, the bodies that surface, over millions of years, out of this embeddedness are flesh odes to past ecosystems. Professor of biological anthropology and neuroscience Terrence Deacon muses, “Adaptive functions are, however, more than just the elements of an entity that respond to the entity’s environment. They embody in their form and dynamic potential – as in a photo negative – certain features of this environment, that if present, will be conducive or deleterious to the persistence of this complex dynamic… In case of dysfunction, the correspondence relationship between internal organization and extrinsic conditions no longer exists. In a crude sense, we can describe this as an erroneous prediction based on a kind of physical induction from past instances. It is in this respect – of possible but fallible correspondences – that we can think of an adaption as embodying information about a possible state of the world.”

Like Mendieta’s silhouettes, like those ancient footprints in England, our bodies represent a photo negative of lost landscapes. The absence that by virtue of what it does not contain, opens a portal into past. We can pour plaster into our physical cast and see what comes away. Scientists study our bodies, trying to work backwards to the grasslands in Africa and the early ruminant populations we would have evolved alongside. When did we become human? The answer is always elusive. Perhaps because it relies on a fiction. The idea of a climactic species or ecosystems. When did we become human? Rather, if we are human now, what are we on the way to becoming? Evolution, albeit slow, never stops. We are already physically obsolete, animated relics of lost worlds, imprinting our brief somatic experiments into genetic love letter to a “possible state of the world”.

While our bodies are the marks left behind by lost landscapes, they are also the absence that implies possibility. Exaptations are the term used in evolutionary biology for adaptations that switch function as environmental pressures change. A fossil can become a seed for a new flavor of becoming. Just as the footprints filled with seawater, and Mendieta’s silhouettes grew grass and flowers, so does an absence act like a magnet for more matter.

I think of the Gingko tree, born 290 million years ago, before there were flowering plants, originally mutualistically entangled with extinct birds to carry its seeds. The Gingko still survives, a photo negative of these lost avian lovers, faded landscapes, but also a sentinel of survival, one of the only trees to make it through the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The Tao te Ching instructs, “Thirty spokes share the wheel’s hub; It is the center hole that makes it useful. Shape clay into a vessel; It is the space within that makes it useful…Therefore profit comes from what is there; Usefulness from what is not there.” The wheel of evolution spins, whether forwards or backwards it does not matter. What matters is that we are neither complete nor are we just born. We are the haunted matter of prehistoric grasslands. We are ancient absences that open up the gestational space for unexpected emergence. We are all the love songs of past relationships, weathered down to minerals and sparkling dust. We are all the absences that, like an eddy in river water, draws in the power of the current, the fluid pattern of possible futures.

Sources:

Image from Siluetas by Ana Mendieta

Incomplete Nature by Terrence Deacon

Otherlands by Thomas Halliday

The essay “The Eye” by Paul Shepherd

https://www.pnas.org/content/116/43/21478

https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/the-oldest-human-footprints-in-europe.html

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/10/191007153451.htm

Zhou, Z. and F. C. Zhang. 2002. A long-tailed, seed-eating bird from the early Cretaceous of China. Nature 418: 405–409.

Zhou, Z. and S. Zheng. 2003. The missing link in Ginkgo evolution. Nature 423: 821–822.

This has been the free version of my newsletter. If you choose to support the paid version of this newsletter, you will receive at least two newsletters a month featuring everything from new essays, reflection on writing craft, poetry, excerpts from my upcoming books and projects, mythic research, reading lists, poetry, book reviews to ecological embodiment exercises, playlists, personal updates, and generally a whole lot of funk and texture.

I am overwhelmed with gratitude by how many of you have showed up here to support my work and widen my thinking. Right now you are literally keeping me alive and funding the out-of-pocket medical expenses that allow me to receive IV nutrition and connective tissue specialists.

I am grateful in a way that is wide and deep and low. I hope you can feel some sonorous note of it - the hum and grind of ice relaxing under the sun - in your body. I am sending the song of my thanks your way. I love you all so much

I was describing your work to my sister the other day: “Sophie is to words what Rembrandt was to brushstrokes“. She is a painter, so I suspect she will check you out. Sometimes I surmise the state of the world today has something to do with the fraying of sisterhood. Silverbacks and alphas are no match for a united, embodied and embedded feminine. 🙏❤️

I’m so touched by all of your poetic words. “There is only one pulsing river of becoming.” I’m trained in a methodology of becoming - social therapeutics. Your writings are also very meaningful for me, as I have lived with chronic pain for half of my 70 years. Grateful 🙏❤️🌱🕊️✨