We Live and Die In Real Bodies

Sick Women Deserve Better Stories - A Critique of We Live In Time

“To look these things squarely in the face would need the courage of a lion tamer; a robust philosophy; a reason rooted in the bowels of the earth,” Virginia Woolf from On Being Ill.

“Only certain kinds of sick people make it into art…I’ve also never seen a sickbed scene from the point of view of the person in it. A problem with the sickbed scene as painted by the sick person herself is that it would have to be painted on a canvas with no edges, to be too small to measure, to be too large to contain. It would happen outside of time, happen inside of history, exempt the present from the linear, rearrange substance so that blankness is an element, rearrange aesthetics so that the negative is almost all. That kind of painting would be hard to make.” – Anne Boyer from The Undying

This past weekend I found that my eyes could no longer read another word. I was oversaturated with text. I’d been in a stretch of work and publicity that I’d consciously packed into a narrow of window of time leading up to a series of scans, doctor’s appointments, and potential biopsies knowing they may derail my life yet again. Crunch the work to prepare for a personal apocalypse. Work with mortal urgency then collapse. It’s an unsustainable rhythm. But then again what other rhythm is there for us who are accompanied by the knowledge that no tomorrow is given?

I tried to nap but I was too burnt out even to nap. Swaddled in blankets and still shivering, my glitchy body unable to reconcile the unseasonable temperature fluctuations and wildfire smoke, I opened up my laptop and decided to watch a movie, scrolling through recent releases until I recognized one from the recent social media zeitgeist. We Live In Time, directed by John Crowley with a screenplay by Nick Payne, is an asynchronous story of modern love, motherhood, illness, and loss, starring the well-paired Andrew Garfield and Florence Pugh. As happens more and more these days, a meme-able film still and a few well-placed podcast appearances gifted this film with premature laurels well before general consumption, and we were primed to both adore and sympathize with this attractive duo as they combat cancer and the nuclear family unit.

The non-linear twist on a love story never lets the viewer forget that while Almut (Pugh) and Tobias (Garfield) are blithely falling in love they are also falling into parenthood and then not so blithely falling into the bardo realm of ovarian cancer and death.

First it must be said that I am a sick person and have been a sick person since the age of sixteen. But I have been a lover of stories my whole life and I have always searched for survival models in art. As a child navigating traumatic abuse, I looked for heroines that alchemized violence and got their revenge. As a young girl with ambitions and desires I looked for stories that reflected me back to myself as a grown and successful woman. Was it possible? Could I have my cake and eat it too? Could I survive violence and then get to something beyond survival? Could I thrive? Was I allowed that?

There were roadmaps. Not many. But some. I clutched them like rosary beads. I read and reread stories of female survival and joy. Despite its many flaws, Twilight was one of these stories as was the author Stephenie Meyer’s own trajectory out of housewife drudgery into stratospheric popularity. I wanted to write love stories. I wanted to live a love story.

But then at the age of sixteen I got seriously ill. I got sick in a way that did not resolve – that got worse and weirder and quickly and surgically cut me off from almost all shared experiences with my peer group.

And suddenly I had no stories where I could recognize myself. I was covered in sores, sprouting wires and IVs. Skeletal and bloated. My daily life was disgusting: vomit and bitter antibiotics and infections and painful procedures and side effects.

The only stories I had were A Walk to Remember and A Little Bit of Heaven and A Fault In Our Stars and Love Story.

And those stories did not give me a roadmap to either dignified and spectacular decay or ecstatic survival.

Instead, the precious few films about women with chronic and incurable illness taught me that my illness made me into the perfect narrative crutch. When a young woman becomes ill she becomes the perfect story-selling device: disabled and unable to work, her narrative is put to work reclaiming her lost value. If you can’t serve men dinner, you can serve them moral superiority and a hero’s journey. These stories robbed me of personhood and taught me that as a sick woman I was there as part of a male partner’s evolution. I was there to temper him with grief. To perform youth and fragility and die before anything like real humanity or suffering could potentially ooze from my orifices and ruin the hagiography.

There is a shadow cousin to the Manic Pixie Dream Girl. The Sick Yet Spunky Girl. The key word here is Girl. Even if she gives birth or crosses into the third decade, she will not be allowed maturity or authority. She is perpetually maiden in her fragility.

She will always be killed off in the third act.

I got sick of movies about sick women pretty quickly. I looked for better stories. Memoirs by women for women about what it means to survive not only capitalism’s sexist ecocidal death grip but also personal apocalypses that neither fully claim nor release us: those long-term degenerative diseases without immediate end or cure that take your youth and femininity gradually in visible and humiliating ways.

But I still longed for love stories that included me in all my symptomatic complexity. As I entered a partnership in my early twenties, I found myself once again looking for stories that showed me how to navigate long-term illness with a lover.

That partner then left me after a devastating doctor’s appointment where the specialist in my condition catalogued the expected breakdown of my body. Within two months our long-term relationship had broken down. There were many reasons for this breakdown but the appointment with the doctor felt like a clear moment of rupture. He liked the idea of a Sick Spunky Girl who let him perform his paternalistic fantasy while actually requiring constant care. The Sick Spunky Girl lets him feel powerful while actually paying the bills, cooking him dinner, cleaning the house, and keeping the ship generally afloat. He liked how I assisted his narrative. I’m sure I’m part of his narrative now. Too sick. Too much. But he Evolved Into His Mature Self Through Caring For Sick Spunky Girl.

Bullshit. Let us as sick women reject how we have been eaten by male narratives.

The reality of my potential decay and surgeries and reproductive inefficiency and eventual care needs were less sexy. The reality that he might actually have to care for me rather than using my illness as a narrative crutch scared him right out the door.

That was the first thing that really struck me about We Live In Time. In a time when women are rejecting sex and relationships, cynical as we confront dwindling reproductive right and horrifying sexism from our every romantic encounter, the first fantasy of We Live In Time is the Genuine Love Marriage.

I’ll argue that it’s only a genuine love marriage because it doesn’t last long enough. Almut only stays alive long enough to produce a child, provide Tobias’ character with evolutionary catalyst, and make every other sick woman watching feeling hideous and unlovable by comparison.

Almut and Tobias don’t get divorced. They are a marriage success story! Turns out we can all avoid divorce if the woman just dies. And then the grieving man doesn’t have to be an adulterer or an abandoner. He can take up his esteemed mantle as Widower and marry a younger woman.

Until she dies leaving him free to begin the virtuous cycle. It’s like Henry the VIII where the murderous king doesn’t have to behead wives to marry again. Instead, he just stands aside and lets a complex network of pollution and injustice give them gender-specific cancer. The he uses his sympathetic role to capture the next unsuspecting victim.

Yeah, Almut has ovarian cancer in the movie. Illness is always political and women suffer misdiagnoses and sexism at the hands of medicine every day, delaying treatment and subsequently upping their chances of mortality. Ovarian cancer is easy to diagnose and yet women are often not diagnosed until the disease has metastasized, already in a late and untreatable stage. Women’s pain is ignored until it becomes dramatic enough. Until it ensures their narrative will be useful to someone else.

I’ve been taught my death is consumable. As long as it isn’t messy. As long as I remain thin and fragile.

What does that do to us – by us I mean sick women – when we are forced to watch and read these stories?

The second fantasy of We Live In Time is the fantasy of a male partner who stays. Who does not leave.

We know that in reality getting sick puts women at a significant risk of abandonment by a male spouse or partner. A 2009 study published in Cancer the Journal found that women are six times more likely to be separated from their partner after a cancer diagnosis than men. The study concludes that to be a woman with a serious medical illness was a strong predictor of abandonment.

The caretaker cannot require care. Or if she does it must be clean and minimal and cinematic and then she must die so the man can move on and marry someone else.

If I sound feisty let me be honest that I am thirty-one years old and I am very sick. I am confronting intersecting comorbidities that make care difficult and expensive and put a cure and health well out of reach.

I am desirous of a partner like the fantasy in We Live In Time. One that doesn’t leave. That takes care of the kid. That wants to have a kid with a sick woman. I want it so badly it hurts.

But I also don’t want to die. I don’t want to be Almut who pukes twice demurely and shaves her head to signal chemo but doesn’t display any of the disgusting paroxysms of disease I know so well.

More and more I think that when it comes to both disease and death, the dignity is in the details. The gross ones. What color is your pee? What face do you make when you ugly cry? What kind of puss? What kind of cramp? How itchy were you? What did it feel like when they missed the vein with the needle? When the medicine removed the soft lining of your throat? When you bled from your belly-button and ears? Give me the specifics. Please help me understand the hurdle of getting through a single night of agony and nausea that contains within it a thousand and one nights.

Watching Florence as Almut decline delicately and asynchronously I thought that the time gimmick of the movie was a secret erasure of what illness actually does to women.

We get to see Almut young and healthy and beautiful again and again interspersed with shorter shots of her bald and dying. But Almut doesn’t get the respite of her younger self. She loses her hair, her ovary, her career, her life and she never gets them back.

A story about a sick women better honor that loss and stand with her in it. It better leave behind the beauty and fertility and hair and come into the details of decay and death. We Live In Time isolates Almut and erases her experience again and again. It shows us nothing of her actual suffering and constantly returns to her original youth and bubbliness.

I finished the movie shaking with grief and sadness. Why are we still congratulating and awarding and producing stories that get off on killing women – in particular young female mothers again and again? What is this kink? Who is it serving? It’s certainly not serving as an accurate representation of women’s experience with chronic and terminal illness.

I felt, watching We Live In Time, like someone watching porn who realizes Wow, I guess someone has this kink but it definitely isn’t me.

But then as you keep watching your stomach sinks. Someone enters the shot that is your stand in character in terms of age, gender, and chronic illness.

But wait. This kink centers on me dying.

What happens when our fantasies are about erasing and fetishizing the end of someone else’s fantasies?

Most Sick But Spunky Girl stories are really just snuff films.

Is there a version of We Live In Time where we actually live in real time with Almut through the end-stage of her illness and see how difficult that is for a spouse and a child? What would the film look like if it centered Almut?

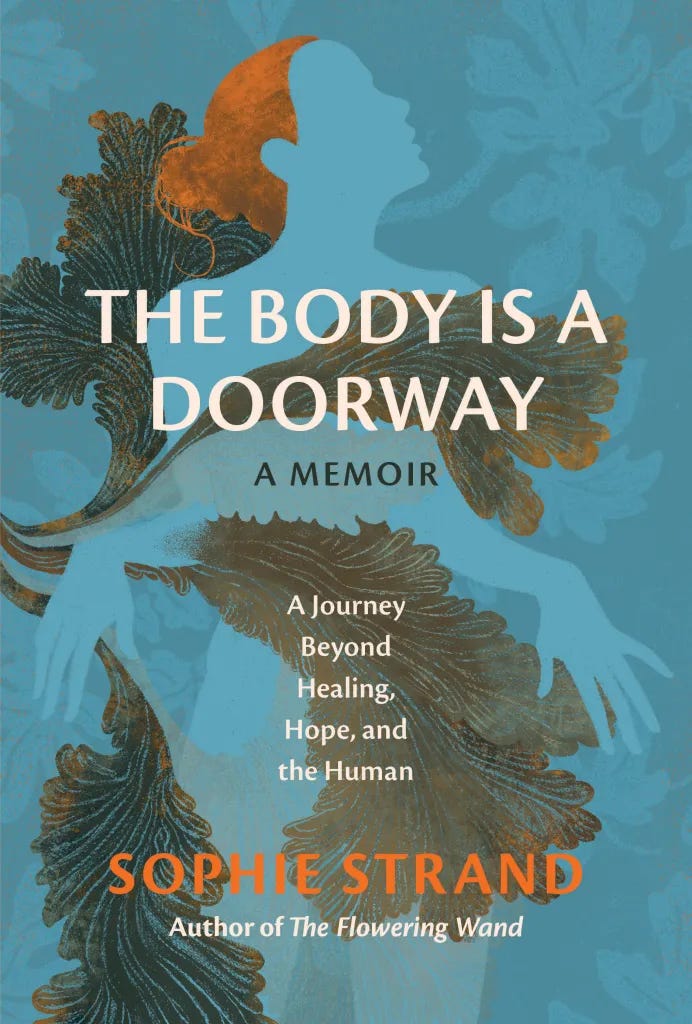

I am struggling to imagine a life where I might decay and die and also get to live and thrive all at the same time. I am looking for better stories. I love fantasy. But let it be a fantasy where I am fully present in all my weird, sick, gross nuance. I am hoping my upcoming memoir The Body Is a Doorway provides openings if not answers to some of these concerns.

What movies and art and books have given you better stories of illness? Let’s compile a list!

This has been the free version of my newsletter. If you choose to support the paid version of this newsletter, you will receive at least two newsletters a month featuring everything from new essays, reflection on writing craft, poetry, excerpts from my upcoming books and projects, mythic research, reading lists, poetry, book reviews to ecological embodiment exercises, playlists, personal updates, and generally a whole lot of funk and texture.

I am overwhelmed with gratitude by how many of you have showed up here to support my work and widen my thinking. Right now you are literally keeping me alive and funding the out-of-pocket medical expenses and specialists.

I am grateful in a way that is wide and deep and low. I hope you can feel some sonorous note of it - the hum and grind of ice relaxing under the sun - in your body. I am sending the song of my thanks your way. I love you all so much.

This is a stunning, deeply needed post. Thank you for your powerful writing (and the enlivening and moving workshop last weekend). I hesitate to include this because I know nothing except what I saw in a Netflix documentary, of all things, and it is NOT covering many of the elements of story you’re searching for, as am I. But one story I followed and feels important is the one co-told by journalist, musician, and best-selling author Suleika Jaouad. Of course we only see shots of the sanitized version of her suffering, but we do hear her speak about it, alongside her long-term love and husband, Jon Batiste. Yes, they have tons of money, fame, resources, all of that. But Ive been moved by their love story amidst the clear suffering, a small part of which she shares, and how Jon seems to centre her experience. I’m sure I’m missing a lot from the way the story was told, but for me it felt different than the many you mention.

One of my favourite musicians, Halsey, just released a new album, most of which chronicals her recent battle with lupus and a blood disorder. It is so good. "The Great Impersonator"! 🩵🩵